ABOUT three decades ago, many parts of the African continent were flashpoints of conflict, although much of this had to do with liberation wars, especially in Southern Africa.

This was true particularly among some countries that make up the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the last region to either win political independence or attain majority rule.

Today guns have fallen silent in Southern Africa and peace has been restored. However, this is not the case with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which is also a SADC member state.

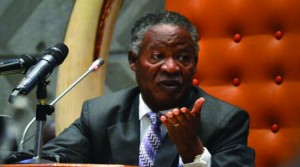

In view of this, there is urgent need to heed President Michael Sata’s call for more support from all partners in the implementation of peace and security in the DRC and the Great Lakes Region generally.

Speaking at the Fourth Regional Oversight Mechanism on the margins of the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in New York, President Sata said although restoration of peace initiatives had reached implementation stage, more effort was needed to completely weed out conflict in the region.

Mr Sata’s call has been echoed by UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon, who says peace implementation on the African continent has been worryingly ‘too slow’, making some rebel forces take advantage to further their negative influence.

Like President Sata, Mr Ban wants African leaders to accelerate efforts towards restoring peace and security, which he says can help foster sustainable development in Africa.

Conflict in the DRC particularly has raged on for a long time. At some point, it had actually involved some seven nations, whose reasons for their involvement were varied, ranging from the desire to have access to basic resources, including water, to control over minerals.

In addition, various national and international corporations which were said to have had an interest in the outcome of the DRC conflict were said to have been involved in fueling and supporting the DRC instability.

The United Nations and other international organisations described conflicts in the Great Lakes Region as being the world’s deadliest since World War 11, with the DRC alone recording some 5.4 million human deaths by 1998.

The fact that the DRC conflict has continued to date means an increase in the number of human casualties although, of course, some of these people may have died from non-violent causes such as diseases.

The Great Lakes Region is not the only African region, though, that has been experiencing conflict. For instance, in West Africa, the Niger Delta in Nigeria is another, although the most vicious is currently being waged in the north of that country between government forces and fighters of the Boko Haram, who are still holding captive more than 200 schoolgirls kidnapped earlier this year.

North Africa has also experienced protests in such countries as Tunisia and Egypt while rebel factions are currently fighting in Libya.

There are also conflicts in Somalia, the Central African Republic and South Sudan which African Union Commission deputy chairperson Erastus Mwencha alluded to, while similar ugly scenes have been witnessed in countries like Cote d’Ivoire and Liberia, leaving thousands of civilians killed.

Some estimates by international organisation, Oxfam, put the number of people in dire need of food, clean water and basic sanitation at 12 million, as a result of these conflicts.

Meanwhile, in 2010, more than nine million refugees and internally displaced people were estimated to have been the direct consequences of conflicts in Africa.

Commentators remarked that if this scale of destruction and fighting was in Europe, people would be calling it World War III with the entire world rushing to report, provide aid, mediate and otherwise try to diffuse the situation.

President Sata and Mr Ban have, therefore, a valid point when they call for support in the implementation of peace and security in the DRC and the Great Lakes Region where conflict calls for immediate world attention.